How does the U.S. identify its adversaries, and should it?

Part 1: The mysterious, anonymous path to defining “adversary”

There is a part of the human brain that wants/needs to list things. This is why some of us are addicted to Wikipedia or why I compulsively read the Book of Lists as a kid.

Many Americans might assume the United States government keeps a list of its adversaries, recalling the Axis Powers from WWII and President Bush’s infamous Axis of Evil. But no, it does not. Or does it?

There is the question of whether the United States SHOULD list adversaries, and who those might be. That will be the subject of part 2 of this piece. In this part 1, I look at the recent trend of defining adversaries and the ad hoc (thus, not deliberative) way it came about.

Congress did not write bad guy lists into law until recently.[1] Of course, the Executive Branch in its plethora of statements and reports, notably he annual Intelligence Community’s Annual Threat Assessment, tells Congress and the public which countries it thinks are acting like adversaries. It makes lists of countries pursuant to requirements passed by Congress, such as non-market economies under Jackson-Vanik, major non-NATO allies, or tiers of anti-human trafficking compliance. But Congress generally did not name them, until now.

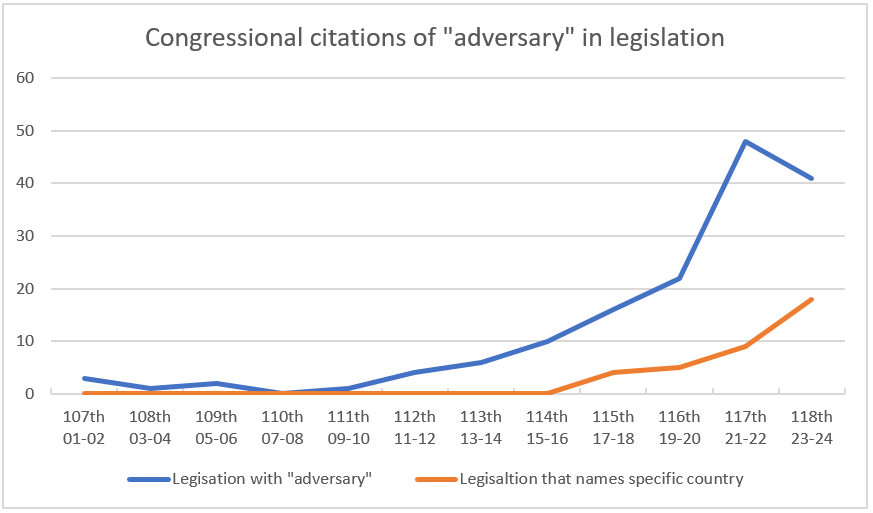

“Adversary” is now a hot word and Congress is addicted to it, as the following chart shows. In the 2000s decade, the number of pieces of national security legislation containing the word “adversary” or “adversaries” was minimal. In the 2010s, there was a gradual increase. Since 2020, it has exploded: 48 bills in the 117tth Congress (2021-22) and 41 so far in the 118th (and we’re not even half-way through).[2]

Members of Congress are even more addicted to specifically naming countries they consider adversaries. This wasn’t even a thing until 2017, and almost half of the relevant legislation introduced this year (18 of 41 bills in 2023) names adversaries.

Definition of “adversary” – who wrote it?

The best I can tell, the first time that the federal government, by law or regulation, sought to define “adversary” was in 2019. And it is not where you would expect. On May 15, 2019, President Trump issued Executive Order 13873 aimed at preventing foreign adversaries from exploiting vulnerabilities in the information and communications technology supply chain. Section 3(b) of the Order said:

“the term “foreign adversary” means any foreign government or foreign non-government person engaged in a long‑term pattern or serious instances of conduct significantly adverse to the national security of the United States or security and safety of United States persons;”

This definition was included again in President Biden’s 2021 update of that EO.

Who wrote this definition? We aren’t able to tell from the public record. As with any Executive Order, this one would have gone through an inter-agency process, although it should be noted that the Department of Commerce was the lead agency, not State or Defense (I’ll come back to that).

This “adversary” definition is copied…

Within two months, this definition works its way into legislation, in identical bills introduced by Rep. Mike Gallagher and Sen. Tom Cotton in July 2019 relating to 5G networks and Huawei.[3]

…becomes law (opaquely)…

Just a few months later, the definition works its way into law. The process is opaque, however. Then-Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Frank Pallone, introduced H.R. 4998, the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act, on November 8, 2019. The committee swiftly marked it up on November 14, and formally reported it out with a report on December 16. Neither version included any language about adversaries. On the same day it was reported, the full House considered and passed the bill. But what passed was a new version with a new section 8 entitled “NTIA program for preventing future vulnerabilities,” which included the definition of adversary identical to the EO 13873 text. This version passed the Senate and was signed into law on March 12, 2020.

It is not unusual, although not really regular order, for bill text to be changed in this manner. We do know that it would have required concurrence by the majority and minority leaders of the committee.

The odd thing is that, as written, the “adversary” definition only applies to section 8 relating to the NTIA program, not to the bill in its entirety, much less to the rest of the federal government. And yet it has come to be accepted as such.

…and becomes the inadvertent standard.

Since 2020, 13 pieces of legislation have been introduced that include a definition of “adversary that specifically cites section 8(c)(2) of the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act (Public Law 116-124). An additional seven use the text of it.

Let’s recap how we got here:

The President issues an Executive Order on telecommunications security which includes a definition of “adversary.”

Members of Congress start using this definition when writing legislation.

The definition gets air-dropped (outside the committee process) into a telecommunications security bill that becomes law.

The definition applies only to a specific NTIA program.

Members of Congress cite this now-statutory yet extremely narrowly-applicable definition when introducing legislation on a wide variety of national security topics.

For subject matter as weighty as how the United States makes policy regarding foreign adversaries, this seems like a very tangential if not reckless way of going about defining “adversary.”

If we are to have a definition of “adversary” (my dubiousness will be addressed in part 2), then it should be with national security professionals in charge of the process, not the telecom folks. From the Executive side, the State Department should lead the process, with input from DOD and others. In Congress, it should be the Senate Foreign Relations and House Foreign Affairs Committees in charge, not Energy and Commerce. In both cases, the process should be robust and deliberative, not quietly tucked into a telecom bill based on language from a telecom Executive Order.

To be fair, these entities may have had a chop at some point: State during an inter-agency process on the EO, and SFRC/HFAC during the legislative process (although unlikely as neither had jurisdiction). But based on my experience in both the executive and legislative branches, I expect any input to have been cursory at best, not with the scrutiny and seriousness required.

So the take-away here is to ask Congressional offices to think twice before citing Executive Order 13873 or the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act when trying to define “adversary.” And I also ask them whether they should (see part 2).

I also hope that the national security committees on the Hill would realize their prerogatives have been scooped here and spend some time and effort on debating whether and how the United States should define “adversary.”

[1] Admittedly my research was not exhaustive. If I am wrong, please give a shout and a citation so I can correct this.

[2] This data is based on the number of search hits (bills, resolutions, amendments) for the word “adversary” or “adversaries” in Congress.gov. Non-national security legislation was excluded.

[3] Curiously, these two Members introduce companion legislation in March 2020 that cites EO 13873 rather than use the textual definition of adversary.