Retcons and revisionist history: the silly way China is politically weaponized

Those delegitimizing Walz’s ties to Chinese people evoke yellow-peril racism

I recall sitting in a meeting with Phil Crane, the Republican House member who chaired the Ways and Means Committee’s Trade Subcommittee at the time (1999 or 2000). He had just returned from a several-days trip to China and was telling of the marvels of economic dynamism he witnessed. He made these arguments in support of the bill that granted permanent normal trade status (PNTR) to China, which facilitated its entry into the World Trade Organization and removed the human rights conditionality from the U.S.’s trade policy to China.

This anecdote sticks in my memory because Crane was trafficking in the Tom Friedman Fallacy, where a person claims to become an expert on a country’s trajectory after spending a few curated days in a city or two. This trope is often invoked by those who have actually spent years in China getting to know its people to discount those who declare wisdom from a Beijing weekend.

But the anecdote reawakened as I watched the attacks on Tim Walz for having spent time in China and getting to know its people. The most recent effort is by House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer, who is using taxpayer funds to investigate Walz’s “longstanding connections to Chinese Communist Party entities” and demanding the FBI get “information, documents, and communications” related to those entities Walz engaged with.

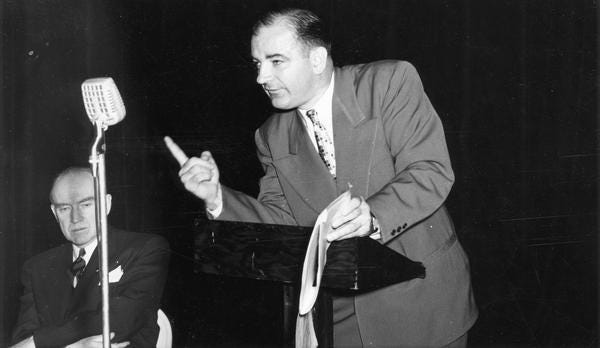

This is dangerous and puerile. For one, it is a pure McCarthy-esque Red Scare tactic, based on a premise that anyone with a China connection is suspect. Second, it is silly revisionism, a cheap retconning of history for a nakedly political purpose. I discuss both:

“Are you now, or have you ever been, in contact with a member of the Chinese Communist Party”

The attacks on Walz for his “35-year relationship with Communist China” are predicated on the notion that any contact with China in that period makes you a risk. Let’s unpack that:

Implicates millions. How many Americans have been to China or interacted with a Chinese national over the past 35 years – students, artists, athletes, sales people, business executives, mayors, Members of Congress? Millions. Are they all suspect now? But Chairman Comer only suspects Tim Walz, for some reason. No one else who has connections to the CCP. Such as Elon Musk. Or Jared Kushner. Or Peter Thiel. Or Jeff Yass. Or Stephen Schwarzman. Comer isn’t calling the FBI on them. Why not?

McCarthy-ism. Using a committee chairmanship to push law enforcement to investigate a political opponent on suspicions (however bogus) of association with communists. We’ve seen this before. History did not judge it well. But here we are again.

Thinly-disguised racism: Holding Walz under suspicion for associating with foreigners is xenophobia. Holding Walz under suspicion for associating with Chinese people (but only Chinese people) evokes yellow-peril racism. Equating Walz’s association with Chinese people as “engagement with the CCP” is factually wrong (only 7% of the PRC’s population are CCP members) and evokes an essentialist mindset that treats Chinese people as a monolith, which derives from racist thinking.

Illogical: Walz spent years traveling in China and meeting people. That experience hardened his criticism of China’s government and empowered his advocacy for human rights of the people of China. That’s not a risk; that’s a benefit.

Retconning yesterday’s China debates through today’s lens: silly and irresponsible

I was a staffer in Congress when it passed the PNTR legislation. My boss at the time was lobbied heavily, by friendly groups on both sides. In the end he voted yes. I concurred in his decision.

Hindsight can be useful to inform future decision-making. But it can also be weaponized in bad-faith political attacks.

Those who voted (or lobbied) against the PNTR bill in 2000 can feel vindication. The core argument that economic liberalization would lead to political liberalization in China did not bear out. They can point to the PRC’s numerous human rights violations today and point to the loss of the leverage provided by trade law in place before 2000. They can say “I told you so.” With this hindsight, I can say now that I would have advised by boss to vote no. But I also believe that, given the facts we knew at the time, my recommendation for a yes vote then was sound.

That 2000 vote was truly bipartisan: 76% of Republicans in Congress voted yes; 43% of Democrats voted yes. Those who claim vindication can’t make it a partisan argument.

There are bills in Congress to revoke PNTR status. I haven’t researched enough to know the economic implications of this. And I would like to hear whether the sponsors argue that revocation would improve human rights. But the part of the argument that “China never deserved this privilege in the first place” feels too convenient to me, especially from those who were not in Congress at the time.

It feels like a retcon. Their arguments apply today’s facts, perceptions and rhetoric to the situation in which U.S. government officials were making decisions a quarter century ago. That’s silly and irresponsible.

I suspect this mode of thinking is a consequence of the choice to routinely substitute “CCP” for “China” (often inaccurately, as I wrote here). It leads to a mindset that perceives the CCP as a monolith, omnipotent and unchanging over time (from 2000 to 2024), which I find analytically unsound and politically-motivated. I also think monolith framing cohabitates with essentialist thinking about the Chinese people, which is racist (see my analysis here).

It is valid to revisit the PNTR decision to inform policymaking toward China on trade and human rights. But let’s recognize when people are doing it merely to score political points or chest-thump “I told you so.”