How does the U.S. identify its adversaries, and should it?

Part 2: Naming specific adversaries is trendy but not wise

Members of Congress want to define “adversary” in legislation but also to specifically naming them. In part 1, I explored the opaque process by which an “adversary” definition made its way from an obscure telecom Executive Order to standard template in legislation. In this part 2, I look at the specific listing of adversarial countries and again ask whether Congress should be doing this.

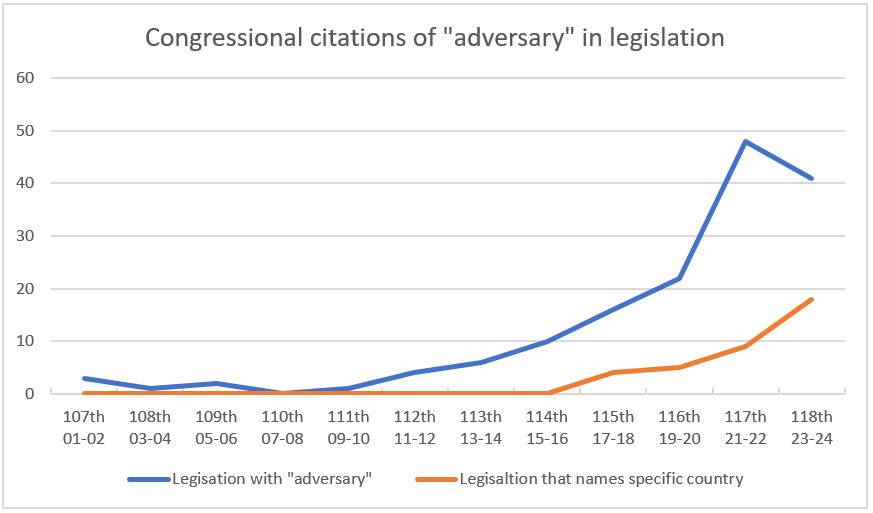

Look at the red line in the chart. Before 2017, the few pieces of legislation that mentioned “adversary” did not cite specific countries.[1] But the trend to name countries has risen dramatically since: four in 2017-18[2], five in 2019-20, nine in 2021-22 and 18 so far in 2023. Nearly half the adversary bills in the current 118th Congress (we’re not even half-way through) name adversaries.[3]

As discussed in part 1, a Trump Executive Order on telecommunications security created a definition of “foreign adversary” that was then copied (mysteriously) by Congress and put into statute in the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act enacted in March 2020. That definition was subsequently used in 21 piece of legislation, 13 citing the law by name and seven using the same text.

And important part of this story is what happened on January 19, 2021, the last full day of the Trump Administration. The Department of Commerce posted an interim final rule in the Federal Register that expanded on the Executive Order by specifically naming the countries applicable under the definition:

The list of “foreign adversaries” consists of the following foreign governments and non-government persons: The People's Republic of China, including the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (China); the Republic of Cuba (Cuba); the Islamic Republic of Iran (Iran); the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea); the Russian Federation (Russia); and Venezuelan politician Nicolás Maduro (Maduro Regime).

The interim rule explains that they relied on multiple sources to come up with this list, including the Intelligence Community’s 2016-18 Worldwide Threat assessments and other federal sources. On the one hand, this represents the mundanity of bureaucracy, an agency outlining the rules by which it will implement a regulation.

On the other hand, this is … WHO? These are staffers from the Commerce Department, not a national security agency, defining the United States’ adversaries. In rulemaking. On a telecom issue. On the last day of an administration. This is not the deliberative process we should expect for such a weighty topic. By its timing and its content (see below) it has a partisan tint. And it is a snapshot, based on assessments from a limited time period.

And yet this obscure rule has become a template for Congress’ adversary lists. Since it was issued, there have been nine bills introduced using the same six-country list, and six others that use the same six countries and add 1-3 more.

Question #1: Should a narrowly-focused regulation written by non-national security bureaucrats form the basis for globally-focused national security legislation?

No. The list may be appropriate for the targeted scope of the regulation. But it did not undergo a rigorous process and was not led by the State Department much less the NSC. It is inappropriate for Members of Congress to import this list into their legislation on broader topics, despite the fact they have already done so.

Question #2: Should Congress be labeling these specific countries as adversaries?

No. While there are cases where it may be appropriate to list countries in statute for a discrete purpose (such as restricting military procurement of sensitive minerals from particular countries), there are good reasons not to list them as adversaries:

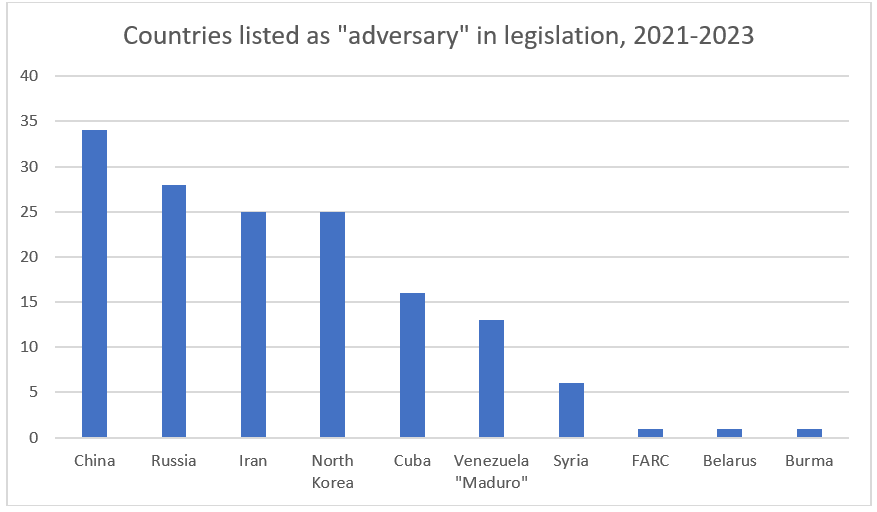

“Adversaries” is imprecise. The dictionary definition of “adversary” as “a person, group, or force that opposes or attacks” fails to encompass the complex nature of relations between government and their people. Take China, the most popular target for the label in Congress (see chart below). If anyone fits the definition, China does. But the governments still talk to each other and share common interests (climate). And it’s hard to reconcile policymakers’ desire to clarify that their quarrel is with the Chinese Communist Party and not the people of China with their desire to label the entire country as an adversary.

Adversaries change. Iran-U.S. relations in the 1970s is the poster child. Afghanistan is a more recent example. But laws have a way of staying on the books long past their utility. The countries listed as adversaries today may not be so in a decade or two. Same with the reverse. Naming names in statute could limit flexibility needed by Presidents in the future and could distort policymaking in favor of outdated postures.

Even “allies” act adversely. Take Israel, long listed as a non-NATO major ally and praised as an ally by many politicians. Yet it is the Israeli government that licensed the export of the Israeli-developed Pegasus spyware that has been used by many governments to spy on activists, human rights defenders and U.S. officials. Or India, which has been accused of transnational repression by killing a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil just after President Biden gave PM Modi a warm welcome at the White House despite the latter’s abetting of authoritarian conduct at home.

“Adversary” lists can be politicized. Anything done on the last day of a presidential administration has the whiff of politics. The adversaries list published on 1/19/21 is no different. It’s notable that one adversary was listed not by country but by name: Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro.

Everyone agrees that the Maduro government is anti-democratic and terrible on human rights. But Maduro has been a top target of Republican rhetorical attacks against socialism and was subject to “maximum pressure” sanctions by the Trump Administration. But in a world filled with abusive leaders (Lukashenko, MBS, Biya, etc.) why is Maduro singled out? And if the purpose of listing him and not the country is show that the United States considers the leadership but not the people as adversaries, why are the people of China, Russia, et al, not afforded the same respect?

The following chart shows the popularity of countries listed as adversaries in bills introduced since the Trump Administration published its list. Not surprisingly, the top six here are the same six from that list.

Of these 35 bills, 31 have been introduced by Republicans, showing a policy preference to list specific adversaries among Republicans and an appeal of using the Trump Administration’s list as a template.

Question #3: Should Congress be naming adversaries at all?

Probably not. While I am personally and professionally sympathetic to the prerogatives of Congress, in this case I think specificity reduces policymakers’ flexibility.

I worry that being specific distorts policymaking by placing the focus on the essence (the country) rather than the behavior. Take the case of Saudi Arabia, which is absent from any list of adversaries, despite the fact that its government has engaged in a wide range of adversarial activities, including assassinating a U.S.-resident journalist (amidst other cases of transnational repression, sentencing) a U.S. citizen to 16 years in jail for tweets, massacring migrants at its border, and exporting extremist ideology, not to mentioning lingering questions about connections to the 9/11 hijackers.

Notwithstanding the geopolitical (or personal financial) reasons why the U.S. government continues to cozy up to the Saudis, the fact that Saudi Arabia is not considered an adversary will mean that fewer resources will be devoted to countering its adversarial behavior than that done by listed adversaries. And by not listing Saudi Arabia, it sends a signal that the U.S. is willing to look the other way on its malign behavior. Which it does and we do.

Similarly, listing a country in whole runs counter to the theme, repeated by Presidents and Members of Congress of both parties, that our differences are with the government not the people of a particular country.

It is a good sign that none of these adversaries list have made it into law, telling us that the gatekeepers on the committees of jurisdiction recognize the downsides. The United States’ national security apparatus was able to do its job before 2017 without having the bad guys chosen by Congress. Maybe it should stay that way.

[1] The methodology involves the set of legislation that uses the word “adversary” or “adversaries” and the subset that names specific countries as adversaries. This is not an analysis of all legislation that mentions specific countries. Nor does it capture legislation targeted at a particular county or countries for actions that could be considered adversarial, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or China’s use of Uyghur forced labor. The purpose of this analysis is to look at how the U.S. government and Congress define as adversary countries, and who.

[2] Not counted here is the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CATSA enacted in August 2017). It was amalgamated bill of sanctions packages for Russia, North Korea and Iran rather than legislation applying a policy to a definition or list of adversaries, so I do not include it this analysis.

[3] It is worth noting that this trend of naming adversaries coincides with the Trump Administration coming into office. It’s beyond my scope to analyze whether there is causation to this correlation, but that would be an interesting research project.