International Relations Heuristic Bias – aka the West-fail-ian trap

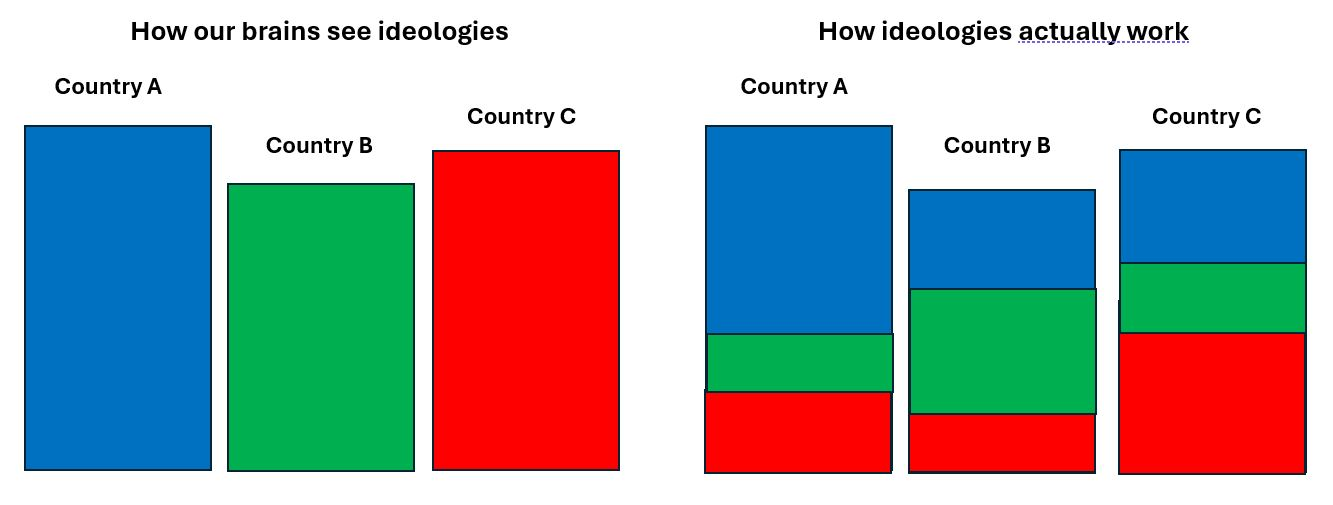

Our brains categorize ideas and ideologies vertically by country. But in reality they flow horizontally across countries

First, a caveat. I am not a political scientist. It’s possible the topic of this post has already been defined, studied and dissertationed by actual political scientists. I make no intellectual pretense. I only write as an armchair foreign policy watcher and occasional policy drafter.

International Relations Heuristic Bias (IRHB) is a term I’m using (coining?) to describe the dynamic in which, because our brains perceive the world as a system of sovereign countries (this is the “heuristic”), we mistakenly think of ideas, ideologies and behaviors as innate within countries rather than flowing across countries (this is the “bias”). We categorize ideas, ideologies and behaviors vertically (by country), rather than horizontally (between counties). This bias warps our policy analysis and formulation, and hinders our ability to identify and respond to trends that challenge systems of governance and social organization. This is the “West-fail-ian trap.”™

The nearly four century-old Westphalian system accords nation-states the highest order of sovereignty and provides the organizing principle for how international affairs are conducted. This system is congenital to the way our minds conceive of the world. It is a necessary heuristic for understanding and communicating about the world because our brains are unable to process much less talk about the eight billion individual units that make up its human population.

(Americans are familiar with this mode of thinking. Because of our (stupid) Electoral College system, we speak of the politics of states in unitary terms. We call Texas a red state even though 44% of its residents voted for the Democratic candidate in the most recent statewide election. We call California blue even though six million of its residents voted for the latest Republican candidate for president.)

Let’s look at the binary of democracy vs authoritarianism.[1] We tend to apply these labels to countries as a whole. So do policymakers. This is a mistake.

Democracy: what’s in a label?

In his first year, President Biden launched the Summit for Democracy,[2] a putative gathering of the world’s democracies engaged in a common purpose of defending against authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and advancing respect for human rights.

It was a laudable initiative with worthy lines of effort on anti-corruption, media freedom, inclusive democracy, etc.

The Summit, as summits are, was organized as a selected list of countries. It was promptly criticized for including several counties who questionably merited inclusion, including those whose leaders have been actively undermining democratic principles in their own countries, such as India, Israel, and Mexico.

Critics noted that, by including such countries in a cohort of democracies, the effort served to downplay and legitimize the anti-democratic backsliding by their leaders. Israel, for example, gets defended as the “only democracy in the region” especially as a way to excuse the Israeli government’s violations of international law in the Gaza conflict. This slogan obscures the fact that the Netanyahu government has eroded democracy in Israel by curbing the power of the judiciary and amending the constitution to make non-Jews second class citizens.

Israel has experienced massive protests against the government’s anti-democratic moves. U.S. policymakers can credibly point to this as evidence of Israel’s democratic nature. Yet those same policymakers refuse to criticize Netanyahu’s regression and repeat the “only democracy” mantra even as they stand side-by-side with the man working to undo it.

A similar story can be told of Modi’s India. American policymakers keep calling it the “world’s largest democracy” despite Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s determined effort roll back democracy. Use of this slogan serves to legitimize the BJP’s anti-democratic march, and does a cruel disservice to the millions of people in India trying to preserve what’s left of India’s secular democracy.

Authoritarianism: spreads like sludge

The U.S. Congress is making a habit of categorizing countries as “adversaries,” which I wrote about here. This list (politically-motivated IMHO) usually includes China, Russia, Iran, Syria, Cuba and Venezuela. Among the drawbacks I identified, having such a list distorts policymaking by focusing on the actor rather than the behavior, and serves to let authoritarian-acting governments not on the list (looking at you, Saudi Arabia) off the hook.

Authoritarianism isn’t confined to a list of countries drawn up by U.S. politicians. It’s a political system suiting ideologies that prioritize hierarchy and power which permeate all countries to varying degrees.

For instance, European far-rights parties (and pro-Trump American political actors) recently gathered together in advance of EU elections in “a global alliance between patriots.” Within their own countries, these parties range from those in fully implementing an authoritarian program of killing free press and rule of law (Hungary) and those trying (Italy) to those with a sizeable presence in the parliament (France and Spain). The reporting on the assembly (which included Argentina’s strident populist Javier Milei) suggest the participants conveyed more loyalty to each others’ ideology than to their own countries’ populations they were elected to lead.

“The Global Anti-Globalist Alliance”

The fact is that authoritarian conduct is not contained by international borders. Just as pro-democracy protests inspire each other around the world, actual and aspiring authoritarians are working together in common cause.

Take Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has created an illiberal theme park and destination for fellow authoritarians Xi Jinping, Benjamin Netanyahu, Vladimir Putin, and Jair Bolsonaro. And for the Conservative Political Action Conference, a prominent Trump-aligned activist group in the U.S., which held its annual conference in Budapest, where participants lauded Orbán’s Hungary as a Christian nationalist, anti-LGBTQ, anti-immigrant promised land. And Donald Trump returned the favor by hosting Orbán at his Mar-a-Lago estate this past spring.

Moscow too. Concurrent with Trump’s personal affinity for Vladimir Putin, Russia has become an idealized “anti-woke” utopia for MAGA conservatives, a redoubt in the struggle against a decadent West that has deigned to allow women, LGBTQ persons, immigrants and Muslims to corrode a Creator-endowed natural hierarchy that places white Christian men at the top. Moscow has become a welcoming home for MAGA expats who want to “escape LGBT ideology” and see Russia as “positive vision of 1950s America.”

And Brazil. Defeated president Jair Bolsonaro deployed the Trump playbook to refuse to accept the results of an election he lost and then incited a mob to storm Brazil’s capitol using advice from senior former Trump White House officials including Steve Bannon. And as further demonstration of the cross-border far-right collaboration, a U.S. Congressional panel gave a forum to Bolsonaro allies to peddle their election denial message dressed up as a human rights issue.

Plus Israel. As I wrote in April, Netanyahu acts not as an ally to the United States but to a favored conservative political faction here. His orientation was on display last week when Netanyahu criticized Biden for not supporting a Republican effort to sanction the International Criminal Court, not unlike an emperor incensed when a vassal state refuses to do his bidding.

These cases demonstrate what the Economist characterizes this as the “the Global Anti-Globalist Alliance.” Authoritarian leaders are readily orienting their actions horizontally, coordinating with fellow ideologues across countries, rather than vertically as leaders of the citizens of the country they are charged to represent.

Complementing leaders’ efforts are networks of far-right activists and influencers. Bruce Hoffman and Jacob Ware wrote last fall about how Americans have become leading exporters of white supremacist terrorism:

“Far-right violence today is increasingly fueled by a deadly combination of ideology and strategy imported from the United States. The “great replacement” theory, which claims that nonwhite individuals are purposefully being brought into Western countries to undermine the political power of white voters, got its start in France, but this kind of thinking has long been a fixture of American white supremacism.”

The New Republic just published an investigation exposing a global network of “right-wing government officials, intelligence operatives, arms traffickers, and journalists” that includes sitting U.S. Members of Congress who communicate via a WhatsApp group started by ethics-deficient soldier of fortune Erik Prince to share messages like “There is only one path forward. Elect Trump.” David Rothkopf just wrote about how Trump’s global network of supporters rallied to his defense following his felony conviction.

Equality and justice go global too

But horizontal ideological flow isn’t limited to the far-right who adore hierarchy and power. The believers in equality and justice do it too. Observe how the social justice protests that emerged in the wake of George Floyd spread around the world, triggering latent thirst for justice in many societies, and the toppling of symbols of white supremacy. More recently, the pro-justice (or pro-Palestinian as some call them) protests at many American university campuses have spread to France, the UK, Italy, Mexico, Australia and elsewhere.[3]

All this reminds us what we innately and empirically know: ideas and ideologies don’t stop at borders, and today they flow at the speed of electrons. But because of IHRB, our policymakers are stuck on the West-fail-ian trap and ill-equipped to understand, analyze and respond.

Correcting for bias

Can we correct for this bias? While we’re stuck with the Westphalian structure for the foreseeable future, we can recognize the IHRB and adjust our lens. Two suggestions:

Strengthen international institutions and apply international law. While enforcement of international law remains on the national level, its precepts apply globally. Its universal principles provide definitions of equality, justice, rule of law and accountability, and its institutions provide for these struggles to be debated and adjudicated and, when national institutions fail, the possibility of redress. International law and institutions were created in response to a previous era of authoritarian ascent and provide a needed source of resilience as we enter a new era.

Craft a people-centered foreign policy. I have a long-standing critique that the business of international relations is driven by the personal relationships between the people who happen to lead nations at that time, who tend to forget or ignore that relations between countries are in reality relations between sets of people who in countless ways exchange information, ideas, connections, images, music, etc. In an ideal world decision-makers would be driven by this complex web of interactions, in what I call a “people-centered foreign policy, rather than their own personal or selfish interests. This is a much bigger topic I hope to explore in longer form someday.

[1] I get that democracy vs authoritarian is a reductive binary of limited analytical application, which the IRHB in part shows, but I’m simplifying here for argument’s sake

[2] This was followed by second and third summits in March 2023 and March 2024

[3] Credit to Daniel Drezner’s The United States Is Exporting Its Social Movements (and Its Social Problems) for the ideas and links on this.